Childcare is economic infrastructure

In the United States, childcare is a personal problem. If you have a child, it's up to you to figure out how to care for them while you work—often at great cost. There's no shared system, just a private market often priced beyond reach, and a cultural shrug that says: "Good luck."

But in most high-income countries, it doesn’t work this way.

In France, families have access to low-cost, high-quality childcare through a national network of crèches and licensed caregivers. In Quebec, Canada, childcare is subsidized to around $10 per day—less than a tenth of what it costs in New York. Singapore funds childcare centers directly and offers progressive subsidies based on income. Even Japan—historically conservative when it comes to gender roles—now guarantees childcare for any child over one if both parents are working.

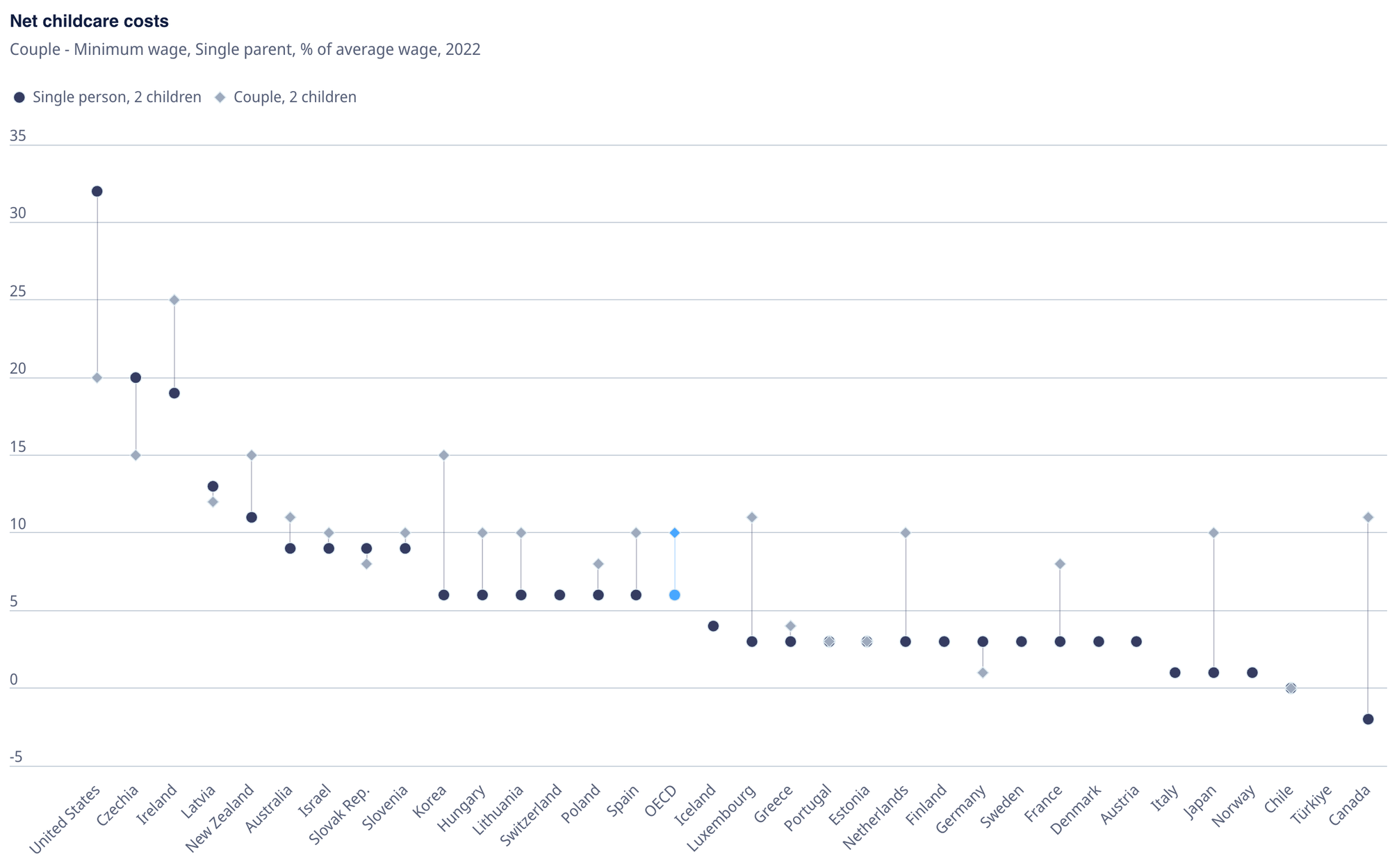

U.S. parents, by contrast, spend 20-30% of their income on childcare.

These systems aren’t just about equity or wellbeing. They’re about economic productivity.

Childcare enables specialization

There was a time when every family grew its own food, made its own clothes, maybe even cobbled its own shoes. Modern economies don’t work that way. We specialize. We trade. One person makes bread while another teaches math or builds homes. Everyone benefits.

Why would early childcare be any different?

Imagine four parents, each staying home to care for one child. Now imagine one of them is trained and paid to care for all four, while the other three return to work in their chosen professions. That’s not just more efficient—it’s how economic systems are supposed to work.

Yet we’ve somehow carved out childcare as an exception, asking each household to solve it alone—as if economic logic simply doesn't apply to toddlers.

This doesn’t mean one-size-fits-all parenting. It means creating a universal system that gives families real options. You can stay home, of course. But if you want to work, your ability to do so shouldn’t depend on luck or income.

The U.S. is one of the few high-income countries without a national childcare system. We spend less than half the OECD average on early childhood services. And the consequences are visible: lower workforce participation among mothers, higher economic inequality, and a labor market that underuses one of its most skilled cohorts.

In cities like New York, the consequences are visible. We lose young families every year not just to high housing costs, but to the sheer logistical and financial strain of raising a child. If we're serious about keeping working families in the city—and building a diverse, resilient economy—we need to treat childcare as the essential infrastructure that it is.

We build roads so people can get to work. We fund schools so that children can learn. We regulate utilities so families can cook dinner and take a shower. These are the basic systems that make life and work possible.

Childcare belongs on that list.

The evidence is clear. In Quebec, universal childcare led to a surge in maternal employment and increased GDP—so much so that the program paid for itself through higher tax revenue. Studies in other countries show returns of 4-to-1 or even 7-to-1 when early childcare is treated not as a handout, but as public infrastructure.

And that’s what this is: not a luxury, not a perk, not a question of personal values. Just infrastructure. A baseline service that helps the rest of the system function better.

We don’t ask every family to grow their own food or repair their own shoes. We’ve moved on—because modern economies build shared systems to meet shared needs. It’s time we did the same with childcare.