People want to be where people are

In March 2022, several colleagues and I flew to Tampa, scouting locations for a potential Justworks office. We visited a series of office parks—low, sprawling buildings surrounded by seas of parking—that were entirely abandoned.

“Where is everyone?” we asked. The real estate broker explained that everyone was working from home. (In that case, why would we set up an office at all?)

COVID was still a factor, but later that day, we visited two mixed-use districts—Tampa’s Riverwalk and Water Street Tampa—and they were buzzing. Offices were open. Restaurants and food halls were full. People were eating, walking, working, talking. These weren’t tourists. They were locals—some who lived nearby, others had driven in from the suburbs just to be there.

It confirmed what I already suspected: Most people don't want to live and work in isolation.

People want to be where other people are. This is true across human eras and societies. It's why my toddler follows me around the apartment as I do chores. It's why people go to restaurants and shows. It's why elderly people live longer and stay healthier when they’re in community.

New York, a city that predates the automobile by several centuries, has a built-in advantage: Many neighborhoods have apartments above shops, bodegas on the corner, and parks or playgrounds a few minutes away. Neighborhood schools connect parents and kids alike. These are the ideal conditions for spontaneous connection—running into a neighbor, seeing a familiar face, feeling part of something.

Midtown: a vertical office park

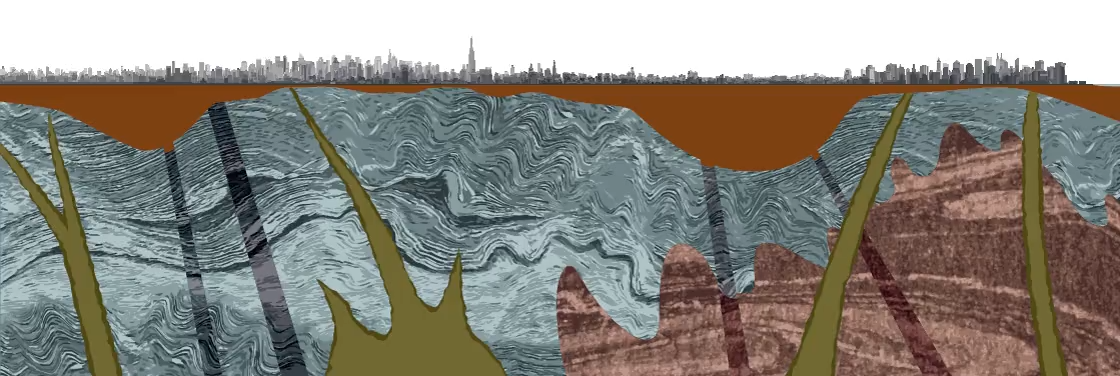

But not all of New York is built that way. Midtown Manhattan, for instance, was designed as a dense commercial engine. Today, it remains dominated by a single use: office space.

As companies continue to embrace remote or hybrid work, the question isn’t just what to do with the empty towers—it’s how to bring life back to these places.

The city’s push to convert offices into housing is a promising start. But towers pose a challenge. Urbanist Jan Gehl argues that once you're above the fourth or fifth floor, you're no longer a part of street life. You can't see the sidewalk. You're less likely to pop out for coffee or run into a neighbor.

This helps explain why neighborhoods like Chelsea, Soho and the Village feel so different: the buildings are low-rise, the streets are walkable, and the line between “inside” and “outside” is porous.

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t build taller buildings. But it does mean we should think carefully about how we do it—how to bring life to the base of a building, how to mix uses, how to create places where people linger rather than pass through.

Residential suburbs: horizontally isolated

The reverse pattern exists, too. In large parts of Eastern Queens, Staten Island, and southern Brooklyn, we see vast residential zones shaped by the logic of the automobile era.

These neighborhoods were largely developed after World War II, when planners and builders believed that homes should be separate from shops and jobs—and that cars would tie everything together. The result: quiet blocks of single-family homes, flanked by wide commercial arterials like Queens Boulevard or Flatbush Avenue, with few walkable destinations or public gathering spaces.

These areas offer space and stability, and residents love them for exactly that. But many neighborhoods lack a walkable center—a plaza, a café, a library branch, a shaded bench outside the deli. A car-dominated commercial strip isn't the same thing. Unless you’re driving, there’s often nowhere to go—and no reason to linger.

If Midtown’s challenge is vertical isolation, these neighborhoods face horizontal isolation. Both are the result of single-use zoning. Both limit our opportunities to connect.

If we want a city where people feel connected, we have to make that connection possible. That means:

- Zoning for mixed use, so that homes, shops and workplaces can coexist.

- Allowing mid-rise housing, especially in places where it can add vibrancy.

- Investing in public space, so that people have a reason to linger.

Urban life doesn’t start in a meeting or a restaurant. It starts at your front door, and that is where the work begins.