Small curb, big difference

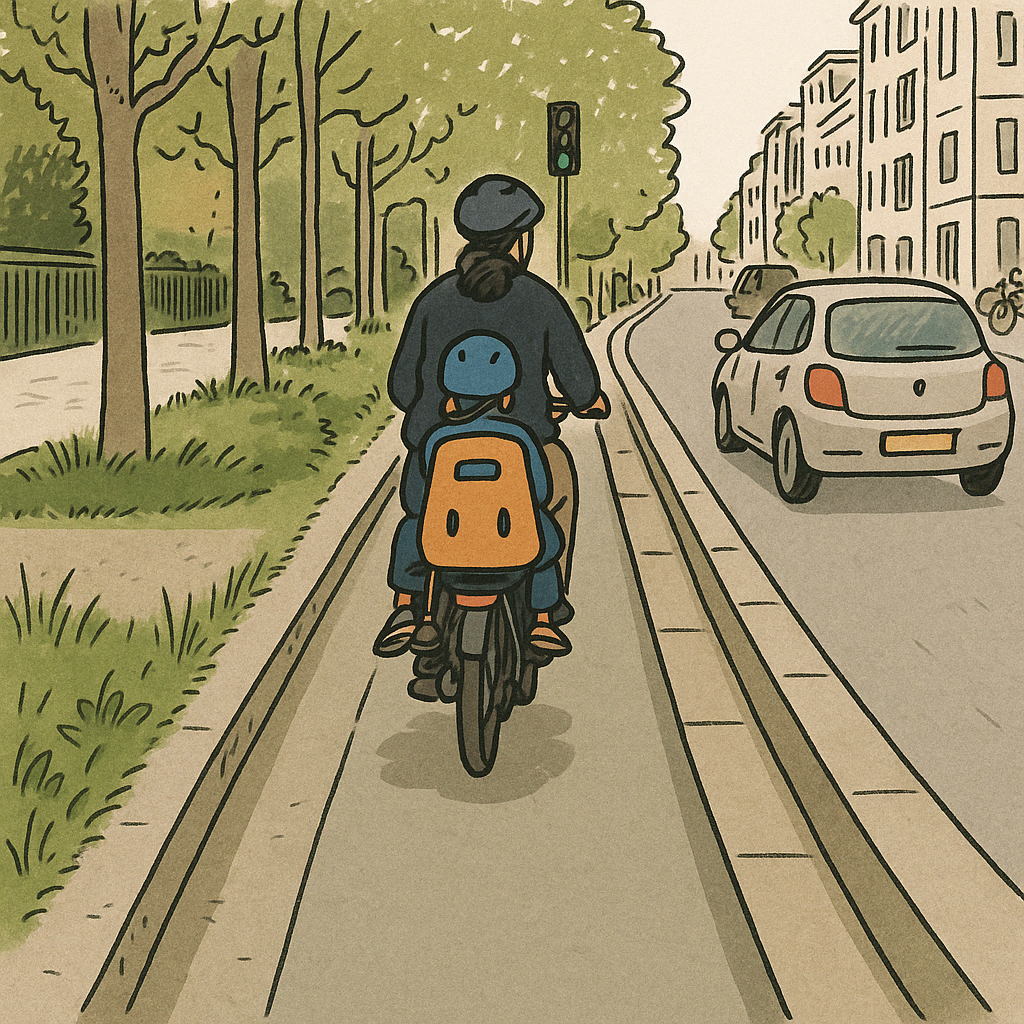

Earlier this spring, I spent a few weeks in Paris. One morning, I was biking right behind a mom who was taking her kids to school:

This is a totally ordinary scene. On weekday mornings, Paris's bike lanes fill with commuters and parents taking their kids to school. The regional government's long-term e-bike rental program, Véligo, even offers bikes that carry two children. It works because people feel safe.

I found myself thinking: Why does this feel normal here, and so rare in New York?

New York has made huge strides in bike infrastructure. Thanks to miles of protected lanes, surging ridership, and Citibike's success, biking is far safer than it was a decade ago. But with a child on board, it can still feel like blood sport. While some parents do ride to school, it's not typical.

So what makes the difference in Paris? There are many factors—cultural norms, driving behavior, enforcement—but one stands out: curbs.

Why curbs matter

Curbs might seem like a small detail, but they're doing a lot of work. On Paris's bike corridors, low concrete curbs separate bikes from cars. It's a modest physical barrier—just a few inches high—but it sends a clear signal:

- Drivers stay out. No more parked cars and trucks forcing cyclists into traffic.

- Cyclists stay in. Narrower, single-file bike lanes encourage calm, single-file riding and discourage wrong-way travel.

- The street is more predictable for everyone—cyclists, drivers, and pedestrians alike.

Unlike paint or plastic posts, a curb creates friction. You can drive over it in a pinch—but you usually won't. And that's the point.

Where New York stands

Most of New York's bike lanes are still just painted lines or flexible posts. That was the right place to start—fast to install, easy to adjust, and crucial for building public support. And it worked. The lanes helped boost ridership and reduce injuries.

But now it's time to make them permanent.

In June 2022, NYC DOT announced a "better barriers" pilot, drawing inspiration from cities like Paris and Copenhagen. Since then, progress has been slow. We need to move faster—especially on streets that already have painted buffer zones.

What to get right

If we're going to start pouring concrete (or placing stone), let's make sure we get the design right:

- Manage lane width. One-way, moderate-speed lanes reduce chaos and improve comfort. A standard lane in Paris is around 1.8-2.0 meters wide—just enough for a cargo bike, but not so wide that it encourages speeding or wrong-way travel.

- Use mountable curbs. These are low enough for cyclists or emergency vehicles or cyclists to cross in a pinch, and low enough for drivers to open their car door. (If the bike lane isn't protected by parking, the curb should be higher.)

- Use wide curbs. A low curb that’s 18–24 inches wide helps cyclists avoid getting “doored” and makes it easier and safer for drivers and passengers to enter and exit their vehicles.

- Add access points. Paris uses curb breaks every 15-20 meters (~50 feet), allowing riders to enter and exit as needed without disrupting the continuity of the lane.

Some new NYC bike lanes are wider and two-way. While well-intentioned, they encourage faster riding and wrong-way movement. That's not the kind of network most people feel safe using. In bike lane design, narrower is often better.

The takeaway

Curbs aren't glamorous. But they matter. They turn bike lanes from suggestions into commitments—and that's what families need. If we want biking to feel normal for everyone, not just the fearless, we need to stop painting lines and start building curbs.