Could we simplify outdoor dining?

As brutal as the early days of the pandemic were, they also forced New York to try things it normally wouldn't. New York moved at light speed to launch its "Open Restaurants" program in June 2020, less than 60 days after the alpha wave ended.

Everything about the program was expedient: the design, the requirements, and even the construction. Time was of the essence and the city delivered fast.

Since then, outdoor dining has been a subject of passion and controversy. On one hand, they're a great way to enjoy the city and they can expand restaurant capacity (and create jobs). On the other hand, many of the sheds fell into disrepair, moving from vibrant to neglected almost overnight.

The city has updated the program, but it doesn't appear to be going well so far: A few weeks ago, the New York Times recently reported that only 3,200 of the city's more than 20,000 restaurants have even applied for an outdoor permit, citing exorbitant costs and uncertainty. "I'm out $30,000. That's before I can even put one table down," one restaurant owner said. "Think about how many chicken tenders you have to sell [to break even]."

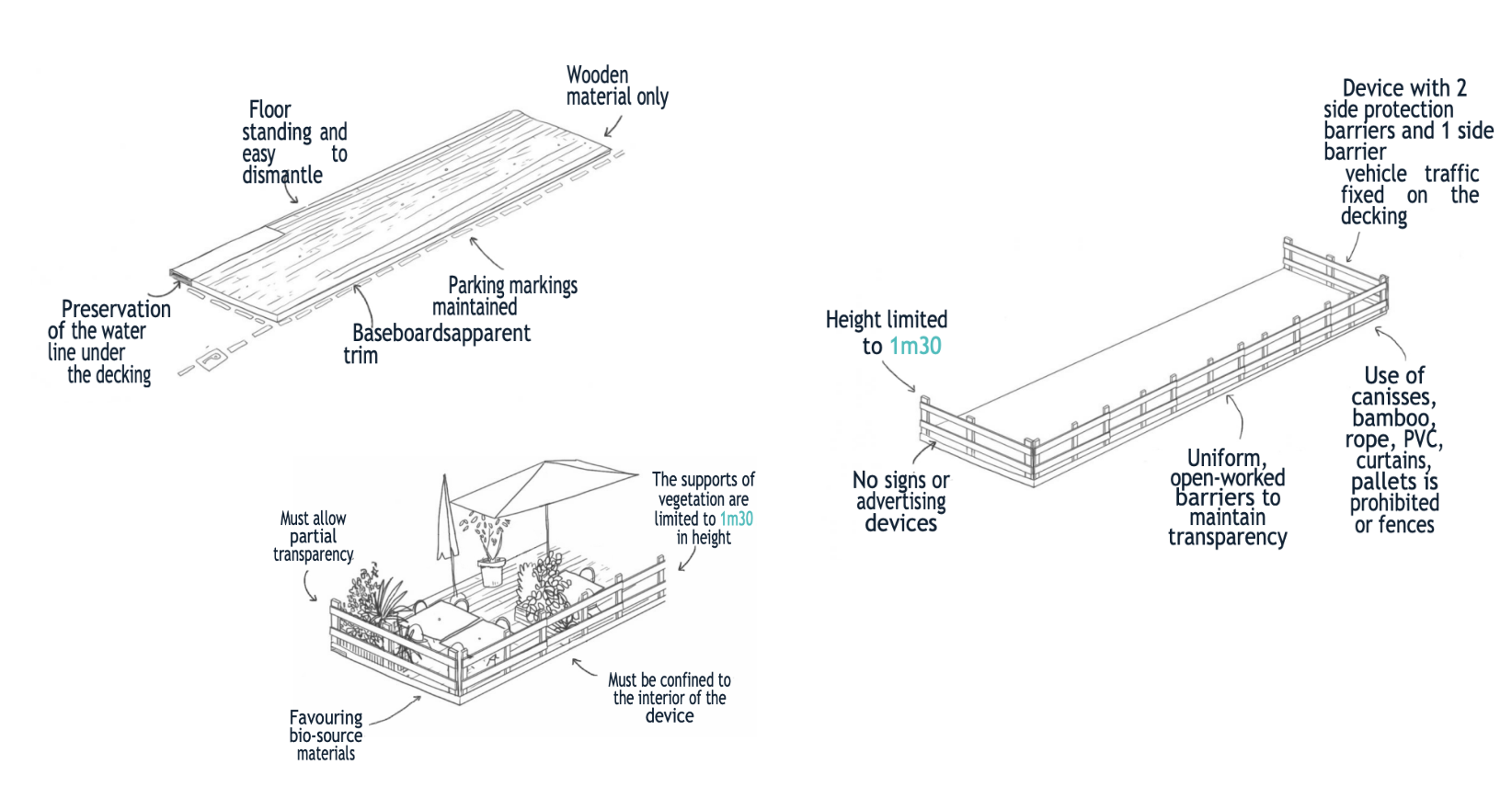

We have taken something that could be simple and made it so complicated and expensive as to be unworkable. By contrast, consider this design from Paris' outdoor dining rulebook:

Paris took a different approach—clear rules, low cost, and a strong seasonal frame.

Their dining platforms are not a replacement for indoor space. They must be built each spring and can be used only from April through October. They must close at 10pm. Electricity, heating and roofing are entirely prohibited.

The simplicity makes them cheaper to build and easier to clean and maintain. Many cafes and restaurants build the platforms themselves, in an afternoon, using less than $1,000 of material. The uniformity forces businesses to compete based on quality, service, and price—better for consumers and more profitable for business.

Our city agencies are paying attention to what other cities are doing! I found the document above on the NYC website.

But by the time a compromise has been reached between agencies, the city council, community boards, and advocacy groups, something simple, pragmatic and broadly beneficial ends up so burdened by process that it becomes unworkable.

This is an example of an area in which the mayor could provide strong vision and leadership—or at least prominently designate a "lead" agency—which would help these myriad constituencies optimize for the overall system first and foremost, rather than each subsystem.

Whether we change our design or not, we need to make sure the process is fast, easy and predictable for restaurants. With that out of the way, we can get back to the fun stuff—like enjoying a meal or drink outside this spring.